Book Review: Aristotelian Liberalism

Most of the books that have shaped my worldview are classic, generally influential works, like The Lord of the Rings, the Summa Theologiae, etc. Even those that are somewhat less famous, like The Machinery of Freedom, are typically still foundational to some particular subculture.

But one book that greatly impacted my worldview is truly obscure – Geoffrey Allan Plauché's Aristotelian Liberalism: An Inquiry into the Foundations of a Free and Flourishing Society, a doctoral dissertation by a PhD student at Louisiana State University.

I came across Plauché's dissertation in 2020, when I was already undergoing something of an intellectual upheaval. I have always been broadly a libertarian, but largely for "empirical" reasons. I loved libertarian ideas like free speech and free markets largely because I'd seen the bad consequences of their absence (half my childhood was spent in Beijing, China) and the good consequences of their presence — Japan's relatively free-market public transport sector producing arguably the world's best public transit, the internet as spontaneous order, cryptocurrency versus traditional financial markets... This is not the blogpost to defend a comprehensive case for libertarianism, but suffice to say my younger self found all the empirical evidence compelling, to such an that I long considered myself as a radical libertarian close to an anarcho-capitalist.

But the usual attempts at libertarian theory from Locke, Rothbard, or Mises always felt thin and reductionistic—for instance, I can't shake the feeling that Lockean property theory or Rothbard's theory of contract as a conditional exchange of property were just-so stories to provide justification for a predetermined outcome (e.g. that people can't just "homestead" all unoccupied land without doing something, or that fractional reserve banking is inherently fraudulent even if it's set up without deception). No libertarian theory seemed to succeed in providing a compelling, "thick" worldview I felt must be lurking somewhere behind all the intuitions so many libertarians share. The deeper problem was that I lacked any clear overall metaphysical worldview, other than the usual motley collection of poorly thought-out ideas unconsciously influenced by the mechanistic naturalism that most people have.

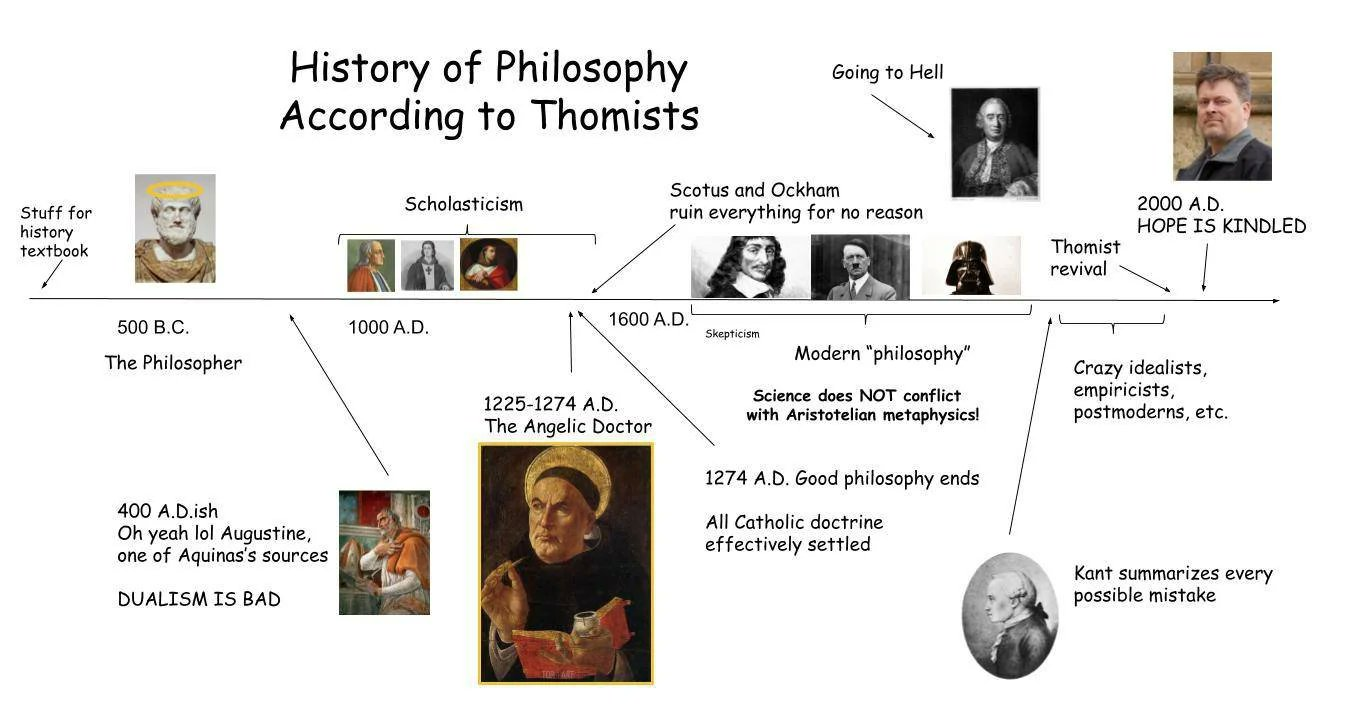

Then in 2020, I encountered Aristotle, Aquinas, and the entire Aristotelian/scholastic tradition (this would eventually lead to my conversion to Catholicism, but that's a story for another time). I was quickly convinced by its internal coherence and deep adherence to common sense. Aristotelianism provided a "thick", logically rigorous worldview with all sorts of intuition-affirming features that are generally denied by more modern philosophies —essentialism (things have an underlying nature, like "human nature"), moral realism, teleology (things have a purpose)... — while sidestepping the thorny problems, like the mind-body problem, that plague modern philosophies. This is all brilliantly demonstrated by the book that first introduced me to this worldview, Edward Feser's Aristotle's Revenge.

I fell in love with almost everything in this tradition, but one thing immediately bothered me: if true, Aristotelianism seemed to demolish libertarianism at its theoretical core. At a theoretical level, libertarian political theories typically started with individual freedom and property and then constructed law and politics as an abstraction over these, but Aristotelianism insisted that humans are inherently political animals who can only flourish in community. Politics cannot be merely for passively defending individual goods, but rather plays a central role in how humans can embody virtue and pursue the common good. More disturbingly to me, at the practical level many streams of thought within this tradition leaned positively authoritarian—think Hilaire Belloc's "distributism" with its emphasis on economic regulation, or the mid-20th-century European corporatist states (like Francoist Spain) that justified themselves with broadly Aristotelian Catholic social teaching.

I could have bitten the bullet and become an authoritarian, but I actually felt like that would be against everything I loved about Aristotelianism and scholasticism. A great paradigm difference I perceived when first learning about this tradition was how deeply it trusted common sense and ordinary human experience. Where modern philosophies often insist that reality is radically different from how it appears (e.g. consciousness doesn't exist, pleasure is the measure of morality), Aristotelianism starts from the presumption that things basically are what they seem to be, humans are basically rational, etc, and philosophy's job is to understand how all this could fit together. It was allergic to reductionism and refused to force false dichotomies.

The problem was that libertarianism being good and authoritarianism being bad seemed like the most straightforward, common-sense interpretation of all the evidence. Common sense was screaming at me that both Aristotelian ideas about human sociality and libertarian insights about freedom and economics were correct. Ditching either one felt like exactly the kind of false dichotomy that Aristotelianism was supposed to cure.

This is when I discovered Aristotelian Liberalism by chance while googling for something else. It seemed to offer a perfect synthesis of my newly discovered Aristotelian/Thomistic framework with my old libertarian convictions, and it felt like one of those satisfying Aristotelian both/ands (like how humans are both material and immaterial).

Aristotelian Liberalism's central claim is that you can embrace a wholeheartedly libertarian vision for society while rejecting the "Enlightenment liberalism" that underlies mainstream libertarianism, in favor of a much older, Aristotelian framework that's very roughly in line with the scholastic natural law tradition. In fact, Plauché claims that Aristotelianism is a far superior foundation for libertarianism than Enlightenment liberalism. In his own words:

“A neo-Aristotelian form of liberalism has a sounder foundation than others and has the resources to answer traditional left-liberal, post-modern, communitarian and conservative challenges… An Aristotelian theory of virtue ethics and natural rights is developed that allows for a robust conception of the good while fully protecting individual liberty and pluralism. Politics is reconceived as discourse and deliberation between equals in joint pursuit of eudaimonia.”

"Supply-side" liberalism

One thing I really like about Aristotelian Liberalism is that it how Plauché explains Aristotelian virtue ethics and the whole Aristotelian approach to politics as a general approach of "supply-side morality".

The idea is that modern theories of politics and ethics are usually demand-side: they begin with what other people, society, etc can claim from us – obeying rules, respecting rights, maximizing utility. Virtue ethics fundamentally inverts this, grounding all morality on maximizing the moral agent's own excellence. In Plauché's own words:

Modern ethical theories often emphasize moral properties—rules or consequences—and focus on the moral recipient, whether that’s an individual, society as a whole, or particular groups. By contrast, Aristotelian-liberal virtue ethics (following Aristotle) adopts a supply-side approach, centering on the moral agent—his or her character and actions. As Roderick Long puts it:

“According to demand-side ethics, how A should treat B is determined primarily by facts about B, the recipient of moral activity; but for a supply-side approach like Virtue Ethics, how A should treat B is determined primarily by facts about A, the agent of moral activity.”

Accordingly, the key question for eudaimonistic virtue ethics is not “What consequences should I promote?” or “What rules should I follow?” but rather “What kind of person should I be?”

This way of viewing ethics has huge implications for politics. If ethics is fundamentally about agents most excellently expressing their rationality, politics cannot be merely about setting up some sort of umpire to enforce social rules. Rather, it's simply the ethics of collective action – the supply-side logic of how to be a good citizen who helps other members of society towards the common pursuit of eudaimonia, or "human flourishing".

We therefore can't really distinguish a separate sphere of political rights away from ethics in general, or in other words "separate the right from the good". Plauché intentionally avoids this cornerstone of "Enlightenment liberal" (and thus mainstream libertarian) politics and wants to construct a more authentically Aristotelian version of liberalism than many previous neo-Aristotelian authors he cited (e.g. Rasmussen) who keep the rights/ethics distinction.

But wouldn't eliminating the boundary between rights and ethics lead to endless paternalism and authoritarianism? If we cannot make a complete distinction between X having the right to do Y, and it being good for X to do Y, what prevents the state, or any third-party, to endlessly meddle in other people's affairs whenever they find them unethical? Unless I have the right to eat as many potato chips as I want regardless of whether it's good to do so, can't the government coerce me to stop eating chips for my own good?

Plauché doesn't think so – in fact, he thinks that this Aristotelian approach to political ethics implies a thoroughgoing liberal society. His key is recasting the famous Non-Aggression Principle central to libertarianism in supply-side terms: respecting another’s rational agency is not primarily something I owe you, but it is an indispensable part of my flourishing:

To resort to initiatory force is to choose to act in a way that is contrary to the requirements of one’s own life and flourishing. It is to choose to act contrary to the way of life that is proper to a rational and social animal. It is to choose to act irrationally or sub-rationally. It is to become a predator and a parasite. It is to choose to live a bad life. The viciousness of initiatory force can be seen from both the supply side and the demand side. From the supply side, the life of a predator or a parasite is not a good life for a human being; it is a life contrary to man’s nature as a rational and social animal. To live as a predator or a parasite is to live a life that is destructive of the values that make a human life a good life. From the demand side, the initiation of force is destructive of the conditions of the possibility of the victim’s flourishing. Thus, the resort to initiatory force is a vice.

In other words, it is corrupts the government agent's character to violently invade my property to take away my potato chips, even if it might be bad for me to overeat. There is no need to posit a "right to overeat"; two wrongs do not make a right.

Plauché's supply-side account of the non-aggression principle also elegantly explains the common moral intuition that liberty from aggression is an inalienable right that cannot be removed even by seemingly consensual arrangements (e.g. selling oneself into slavery). This is because whatever "consent" you might have to be aggressed against does not negate the fact that aggressing against you is bad for me.

One consequence of this virtue-ethical NAP is that it totally rules out any sort of state, at least in the Weberian sense of a monopoly on force. Even a minimal night-watchman state for protecting individual rights won't work, since even such a state must violate the NAP to enforce its own monopoly:

As a self-proclaimed territorial monopolist, even the most minimal libertarian state, should it seek to enforce its claim, must necessarily violate the rights of any of its rights-respecting subjects who prefer an alternative...

...a contract with the state is no more valid than, and is essentially the same as, a slavery contract. This is essentially because the state claims a territorial monopoly on the legal use of force and ultimate decision-making. In both cases (of state contracts and slavery contracts), to paraphrase Spooner, an individual delegates, or gives to another, a right of arbitrary dominion over himself, and this no one can do, for the right to liberty is inalienable. If the subject/slave later changes his mind, exit from the agreement would be barred to him by the terms of the contract; a state contract with the right of secession (down to the individual level), or a slavery contract with the right of exit, would be a contradiction in terms...

The right to liberty is therefore inalienable. It follows that both state contracts and slavery contracts are illegitimate...for the former is attempting to transfer something that is not his to transfer and the latter is attempting to receive and exercise a power to which he has no right.

In short, virtue requires never initiating force, states maintain their monopoly by initiating force against peaceful rivals, therefore enforcing a state is intrinsically immoral. It's not hard to see how along these lines Plauché then quite compellingly argues that consistently applying Aristotelian virtue-ethics leads to a comprehensive libertarian utopia (no monopoly state, free markets, free speech, no "morals legislation"...)

Synthesizing objections

A further strength of Aristotelian Liberalism is the way Plauché deals with objections from various incompatible political views, by absorbing their best ideas rather than merely refuting them, rather in line with the best authors in the Aristotelian tradition (e.g. Aristotle's treatments of incorrect ways of understanding the good life in Nicomachean Ethics, or Aquinas's systematic treatments of objections in every article of the Summa). Plauché typically starts by acknowledging the force of some objection to "liberalism", before showing convincingly that while these critiques decisively undermine Enlightenment liberalism, Aristotelian liberalism emerges unscathed.

One good example is Plauché's treatment of the "postliberal communitarian" critique of liberalism from thinkers like Alasdair MacIntyre, whose ideas also belong to the broader Aristotelian tradition. MacIntyre’s charge that liberal societies, by emphasizing autonomy and individual rights, inevitably lead to atomization and moral fragmentation, destroying the thick community contexts essential for virtue. Plauché acknowledges MacIntyre's point as generally valid, and agrees with MacIntyre that as Aristotelian, "the nation-state is not and cannot be the locus of community", and that genuine morality depends on "an overarching and nested set of inherently social matrixes".

Yet he then argues that MacIntyre's community-centric vision of political life actually fully supports Aristotelian liberalism, rather than the vaguely paternalistic societies his ideas are typically used to justify. Unlike Enlightenment liberalism, it never separates rights and justice from virtue and flourishing, yet on the other hand, Aristotelian liberalism insists that because virtue is learned through practice with equals and truly virtuous actions can never be forced, coercive institutions that crowd out spontaneous associations are self-defeating and can never be conducive to truly flourishing communities.

An even more refreshing example is found in Plauché's treatment of the New Left. I had always though of the New Left as diametrically opposed with both libertarianism and the traditionalist/community-centric ideas of Aristotelianism, but he manages to devote an entire chapter (The New Left and Participatory Democracy) extracting all the good he can out of New Left thinkers. In his view, the New Left correctly points out that (Enlightenment) liberal capitalism, by focusing on negative rights, ignore problematic social structures and power imbalances that cause real injustices despite being formally consensual. Quoting Sidney Lens, he highlights and agrees with the charge that the United States is “a democracy, all right, but a manipulative one in which we are excluded by and large from the major decisions in our lives”, while also agreeing with the New Left's call for a participatory democracy with real involvement "in all areas of life – economic and social, as well as political".

Plauché, however, then proposes that the correct solution to the problems identified is Aristotelian liberalism, with its emphasis on voluntary communities and the joint pursuit of eudaimonia, not the statist solutions preferred by the New Left. He also poignantly points out how the New Left eventually largely embraced becoming part of the state-aligned academic establishment, something he blames on their lack of commitment to hard principles that rule out coercive solutions.

Overall, Plauché's discussions of opposing views made me much more sympathetic to certain decidedly non-libertarian views (some other ones include Rawlsian liberalism and postmodernism) that I would previously dismiss as obviously wrong; in fact, he probably convinced me that many of these views are "less wrong" than classical Enlightenment liberalism.

Too good to be true?

When I first read Aristotelian Liberalism in 2020, my reaction was almost entirely positive. Plauché appeared to align with every intuition I had both that libertarianism had to give an attractive, comprehensive vision of society, and that the Enlightenment principles were horribly inadequate to ground such a vision. I almost felt like Aristotelian Liberalism was the missing manifesto for my own poorly formed political convictions I've been looking for. The fact that he so heavily used Aristotelian virtue-ethics, something with which I was then in an initial infatuation stage, only made it extra cool.

But I had a sneaky suspicion that Plauché's position was "too good to be true". I always treated as a general principle to be more skeptical than usual of evidence that seems to enthusiastically confirm my own views, especially views that few others share — and "libertarianism is substantially true but Enlightenment values are dangerously false" certainly counts.

I wasn't sure exactly what might be wrong with Plauché's argument in 2020. But over the years I've generally become more acquainted with the Aristotelian, and more broadly "classical" worldview, and now that I look back on Aristotelian Liberalism I think that I can point to some specific weak points.

The initial problem I felt is that accepting Aristotelian Liberalism's central thesis seems to violate a general heuristic that I acquired alongside my general shift to a more Aristotelian worldview – when a tradition has remained internally consistent for centuries, it’s vanishingly unlikely that it was sound on all its premises yet catastrophically wrong on an headline conclusion. That is, if dozens of extremely smart people from Aristotle through Aquinas to the neo-scholastics shared the same starting assumptions, yet nonetheless rejected many of Plauché's key conclusions, such as initiating force being intrinsically evil, it's much more likely that Plauché either made a fallacious argument or started from different premises.

I suspect the latter – that there actually are fundamental incompatibilities between the philosophical ground truths of "Aristotelian liberalism" and that of the older Aristotelian political tradition. To be fair, Plauché's work does seem largely in dialogue with comparatively less authentically Aristotelian versions of liberalism (like the neo-Aristotelian ideas those of Ayn Rand, Rasmussen, etc), rather than the broader Aristotelian tradition.

A more serious concern I have is that Plauché explicitly frames his work as a solution to "liberalism's problem". Early in the book he writes:

Rasmussen and Den Uyl … argue that liberalism is unique among political philosophies in having as a central concern ‘the problem of how to find an ethical basis for the overall political/legal structure of society,’ one that recognises the value of individual liberty and can accommodate moral and cultural pluralism and diversity [emphasis added]. They call it ‘liberalism’s problem’ because liberalism has been the only political tradition to recognise its fundamental importance.

But I feel like taking for granted that "liberalism's problem" is worth solving smuggles in Enlightenment-liberal ideas hard to reconcile with Plauché's premises. It's unclear to me why ideas such as "moral diversity" would even be desired given his commitments to moral realism, essentialism, etc. After all, it seems like such a worldview implies that a society, say, neutral between atheism and theism would be the same sort of thing as a society that is neutral between different understandings of the existence of water, where both water believers and water denialists can flourish, and the latter is clearly not conducive to flourishing.

Yet Plauché repeatedly attempts to argue that his model for society would in fact solve "liberalism's problem". He emphasizes the Aristotelian idea that different people have different forms of flourishing, and thus appropriately pursue different specific goods, ways of life, etc even though they are all expressions of the universal human final end of flourishing. Combined with the traditional principle that law governs what is universally obligatory for everyone's flourishing, and not the specific actions that each member must decide in accordance with their own prudence, this get us solidly to a principle that a well-functioning society, especially a large and culturally diverse society (say, the United States), must be neutral between different forms of individual flourishing, different private goods people seek, etc.

But I don't see how a society whose members can freely pursue the full spectrum of objective goods necessarily fits the "liberal" idea of generally "accommodating moral and cultural pluralism and diversity", unless we can somehow equate the objectively different forms of flourishing different individuals have to their respective subjective opinions about what would be flourishing for them. That, of course, seems to take us back to the "Enlightenment"-style moral relativism or neutrality that Plauché explicitly tries to avoid.

There are some other points where the book seems to assume Enlightenment tenets that sit uncomfortably with Aristotelianism, such as assuming that humans are independent equals without unequal, unchosen moral obligations (difficult to square with the traditional Aristotelian understanding where individuals by nature have different moral obligations as occupants of different parts of society, even though insofar as they share a common human nature, they also share common moral obligations), as well as a voluntarist understanding of authority in human relationships as either consensual, or a sort of total slavery and subjection of one will to another (which is a necessary premise for arguing that the illegitimacy of slavery contracts means that any sort of coercion is impermissible), etc.

Overall, I feel like Plauché would have a much stronger case if he simply conceded that Aristotelian liberalism does not need to retain cherished Enlightenment-liberal ideas like value-neutrality or solve "liberalism's problem" to establish a genuinely free society. To me at least, he already makes a strong case that authentically Aristotelian principles – such as the diversity of objectively discoverable forms of flourishing, the requirements the virtue of justice place on rulers, etc – are perfectly sufficient guards against tyranny and authoritarianism without reference to anything smacking of Enlightenment values.

Final thoughts

Despite the weaknesses I mentioned above, I still think Aristotelian Liberalism presents an overall compelling vision of a "free and flourishing society" built on a foundation of Aristotelian virtue ethics. Treating politics as a "supply-side" matter, as primarily about the ethics of being rulers and citizens within a polity, is an extremely refreshing way to think about politics, especially within the libertarian-adjacent sphere where the discussion is almost entirely about negative rights and other demand-side matters. And it did convince me that libertarian moral intuitions and empirical findings are worth harmonizing with an Aristotelian virtue-ethics framework, even if Plauché's particular approach might be flawed.

One thing I would love to see more, though, are people who start out not to justify libertarianism, but to draw out the implications of a traditional Aristotelian/Thomistic account of human political nature while taking seriously the (at least to me) extremely compelling empirical justifications for libertarianism. It's often very disappointing when I read highly respected "postliberal" or "distributist" authors who are by all accounts genuinely trying their best to apply principles drawn from the broader Aristotelian/Thomistic/Catholic Social Teaching tradition, but then betray laughably inaccurate misunderstandings of libertarianism, economics, etc (e.g. that capitalism is an ideology that prioritizes wealth over other goods, that economic efficiency only measures material goods, or that libertarianism and free markets are the same as consumerism). I really wish there were someone committed to orthodox Aristotelianism who nevertheless adopts Plauché's approach to empirical economics:

...I do not plan to attempt a systematic defense of classical liberalism at the level of economic theory and history. There is already a vast literature in this vein and I will be assuming in this dissertation that states and markets operate essentially in the manner described by free market economists, particularly those of the Austrian

School and also to a lesser extent the Public Choice and Chicago Schools.

The only authors I've read who comes close is Edward Feser, a well-known Thomist philosopher who is a self-professed Catholic integralist and postliberal, yet although markedly departing from libertarianism per se, defends a solidly free-market, small-government vision of society against the big-government visions often touted by other "postliberals" in Classical Natural Law Theory, Property Rights, and Taxation:

It is argued that classical natural law theory entails the existence of a natural right of private property, and that this right is neither so strong as to support laissez faire libertarianism, nor so weak as to allow for socialism. Though the theory leaves much of the middle ground between these extremes open to empirical rather than moral evaluation, it is argued that there is a strong natural law presumption against social democratic policies and in favor of free enterprise.

I do wonder, however, whether we can push an authentic interpretation of the Aristotelian natural law tradition in an even more "liberal" direction. I can think of at least a few ideas that broadly "non-Enlightenment" libertarians like Plauché (but also authors like Hans-Hermann Hoppe and David Friedman) emphasize that might allow someone committed to the mainstream Aristotelian natural law political tradition to advocate much more libertarian outcomes: the radical definitional difference between a state defined by monopoly on force and an Aristotelian political community founded on friendship and the common good, the historical viability of "stateless" societies like medieval Iceland (as featured in The Machinery of Freedom), the Austrian approach of treating economics as a non-reductionistic study of human action...

I have not thought too deeply about how these ideas would necessarily intersect with the Aristotelian tradition (and being an amateur in both libertarian and Aristotelianism, I would fail miserably at any attempt at synthesis). It might turn out even given all the above, the "Aristotelian political manifesto" would still be the moderate center-right politics that Feser seems to be imply. But my guess is that "Aristotelian liberalism" is still a vastly underexplored area, and that nobody has come close yet to the correct synthesis.